Curricular design and professional development go hand in hand. As educators, we ask our students to be in a state of continual learning, we must commit to being in that state as well. This can be difficult and ego-bruising and it can be full of joy and self-understanding. I am lucky enough to get energy out of learning new things; it didn’t always line up with what other people hoped I was learning in school but it did build a capacity, and endurance, towards learning new things. As a young adult, my goal was to understand how everything works from machines to people. I was particularly thrilled in high school to find out about the subject of physics which both investigated how things work at a very fundamental level and brought purpose to the study of mathematics (after teaching math, I also enjoyed the beauty of math that did not directly apply to solving real-world problems).

The desire to understand how things work is what kept me in education and drew me towards technology. The school environment is so richly complex and multi-layered that it continues to fascinate me. In this domain alone, you have school priorities, discipline priorities, faculty priorities, faculty capacities, student interests, college expectations, and societal trends all intermixed. Solving the challenge of delivering the optimal curriculum to students is both an exercise in putting yourself in the perspectives of multiple stakeholders and knowing that even if you could arrive at a perfect solution, it would not be perfect for very many years.

At the discipline level, I am proud of how we have created our tech curriculum. It is both flexible to accommodate different students, leveled to encourage depth and thematic across web design, physical meets digital, and programming. We also have clear ties to academic teams, independent curriculum offerings and courses in other disciplines. Arriving at such a balance has been many years of problem-solving in addition to continual assessment as to whether we are keeping pace with society while not chasing ephemeral trends. Over the years, I have given a few presentations on this topic.

At the course level, Evolution of Society, which was created with Matt Delaney and influenced by the Big History Project, showcases what I believe education could be. It is decidedly interdisciplinary, inherently relevant, and tied to the modern world. Students learn how to process a world that is changing with confidence and make predictions about the future (which we hope reduces anxiety for them).

Within courses, every course I teach includes some sort of project. Almost always grouped and with options for creativity in meeting the requirements. This is for a few reasons. One, in the process of building something, you get lots of real-time feedback as to whether or not you understand the topic. Two, it provides for very effective differentiation of student capacities in your course without sacrificing engagement or group cohesion. Third, provides presentation moments for students to teach each other, show their thinking and reflect on their efforts.

Curriculum | Discipline Design

| Designs and implements courses that reflect teacher mastery of their academic discipline and its teaching methodologies | ?+ |

| Designs and implements courses framed by the school’s pedagogical tenets – inquiry, experience, and integration | ?+ |

| Collaboratively designs and evolves course curricula that are reflective of their academic discipline’s philosophy and derivative of the school’s overarching philosophy | ?+ |

| Updates course content to reflect the contemporary world | ?+ |

Focus 2005-2015

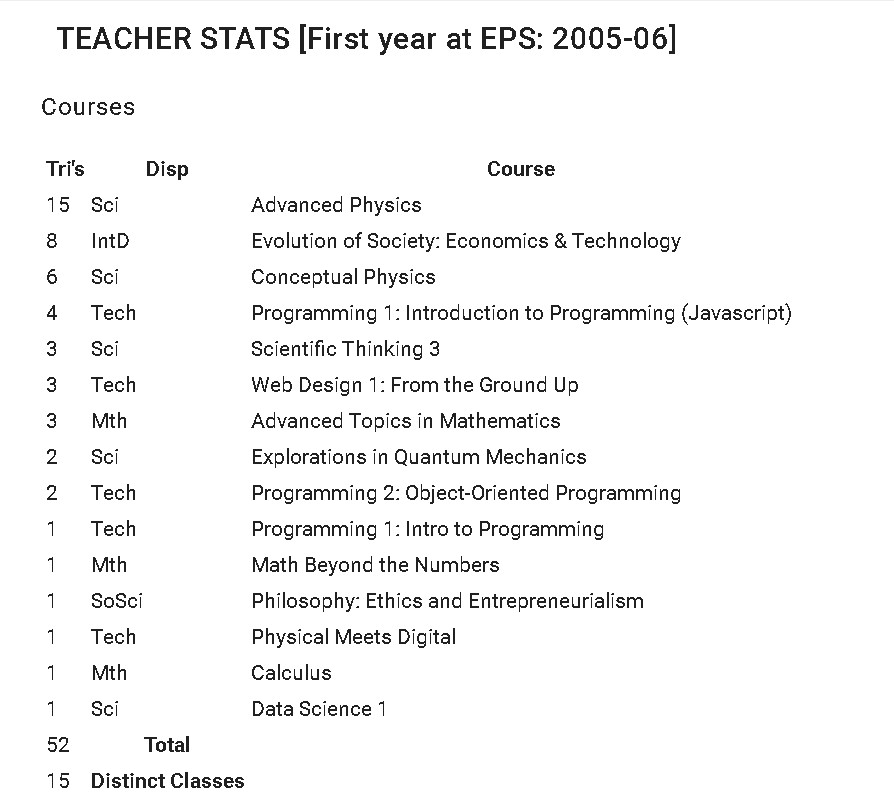

I have taught a wide variety, and levels, of courses in the last 21 years from 8th grade to 12th, from Philosophy to Physics. Some concepts pervade all subjects such as having an arc to your course where students can feel that there is a beginning, middle, and conclusion to their efforts, others are discipline-specific such as science labs or humanities discussions. Student (and parent) relationships are also different among the different disciplines even with the same teacher.

Each course should engage and empower students to be more sophisticated versions of themselves. This can be achieved through relevance to their current, or future, lives and projects tuned to be just outside of what they think they can achieve; stretching their conception of their capacity. Importantly, this is afforded by strong relationships with the subject, teacher, and fellow classmates.

When designing courses, I go through a few steps. First, a deep dive into the content of the course, what are the concepts, ideas, and skills involved in this course and how do they relate to other things in the curriculum or the world. If you are teaching the quadratic formula, you should know how to derive it even if students won’t need to. In physics, you should be able to speak to 2 and 3-dimensional collisions even if you only solve 1-dimensional problems in class. With that knowledge in mind, lay out the ideas and concepts in a sequence that works (often a concept will require other concepts as prerequisites). Then look for ways to have multiple concepts integrated into projects, tests, or papers.

There is a lot more flexibility in sequencing than is initially apparent. As an example, I have taught physics starting with sound and optics and I have taught it starting with forces and kinematics. Both work well. Interestingly, I moved sound and optics to the beginning as students often had an easier time with those topics and I thought it would be a softer transition into physics, which can be challenging for some. To my surprise, that year, students reported the opposite, sound and optics were hard but forces and kinematics were easy. Turns out, the hard part was developing the capacity to think in the ways that physics demands and however you start, it will feel difficult and the association with the specific concepts is not as significant as students (or teachers) think.

The speed of acquisition of concepts for your students is the hardest part of designing a course. You should try hard to estimate it and you should expect to have to adjust significantly. After a couple of years with the same course, provided you took decent notes, you should be pretty close however, always build in buffer days from the beginning. Every class section is different, every year has unexpected interruptions or complications. After early years of being committed to getting to the end of the planned content, transitioning to finishing the experience well (even if I had to drop whole units) left students feeling more confident in the subject, and less stressed as the term or year closed out and with both deeper learning and more confidence. Like a good paper or story, pay attention to the introduction and the conclusion. In the middle there is lots of flexibility in how deep or wide you go, don’t sacrifice the climax of your course by being unwilling to let some mid-course content go.

Mock classes for admissions were an amazing laboratory for designing single-class experiences. Teaching the same lesson dozens of times in a row with different students allowed for many small tweaks to be tested out with a quick feedback loop. Over the course of an admissions season, you could see how many small tweaks could make, collectively, a huge difference in the learning of the students. Once honed, you could also witness how a subtle difference in the student group could make for a far different pace of class (getting through class slower was often due to richer discussion). Additionally, sharing the load with Matt Delaney and later adding Paul Hagen allowed the three of us to collaborate to optimize the class (we also received observation notes from Kristina Damrose and Katie Nikkel).

Program | Professional Development

| Participates actively and constructively in Program Development Day activities | ?+ |

| Presents during Program Development Days and conferences | ?+ |

| Takes advantage of professional development provided by the school | ?+ |

| Identifies and pursues professional development opportunities appropriate to enhancing effectiveness as an educator | ?+ |

I love that part of my job is spent learning. Whether it is at a conference, learning about a new way of thinking or technology, or building something to further my knowledge. I am not only allowed to spend this time, but I’m also encouraged and funded to do so. Being able to share that knowledge with others to engage and empower them is an added bonus.

While my list of presentations, internal and external, is extensive, it is equally, perhaps more, important that I am a solid audience member for others’ presentations. Whether it is noticed or not, it is important to me that I am a focused engaged participant for my colleagues. This has been a multi-year effort that I now feel quite solid on. For me, it is four rules:

- If you are going to be there, be there and be present

- Close the computer (it’s too easy for me to get distracted by a quick task-oriented email)

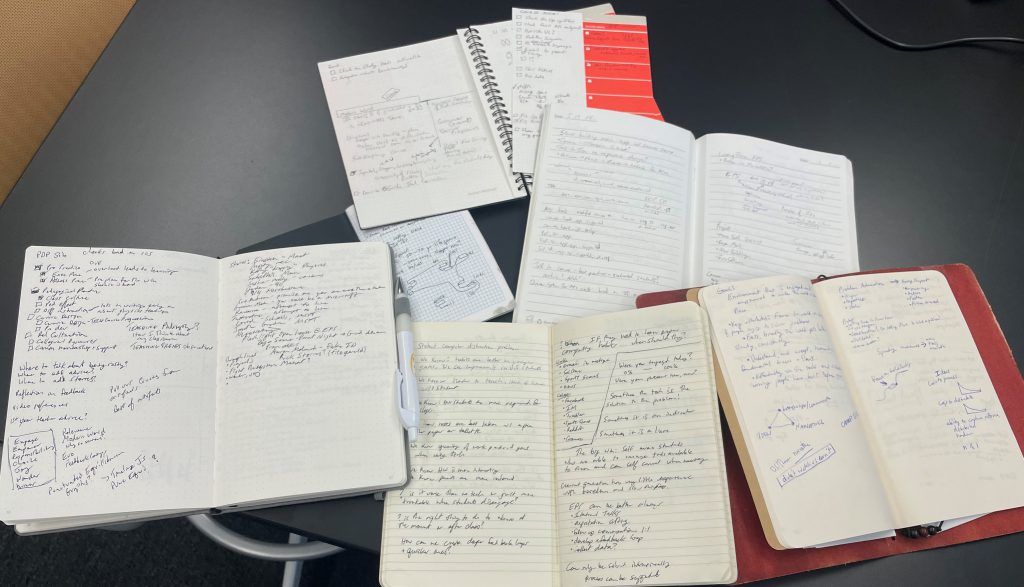

- Bring a paper notebook – when I have tangential ideas or remember something that needs to be done, writing it down somewhere I am confident that I will find it is the only way for me to continue to be present

- Don’t harp on the slip-ups, my job requires me to pay attention to text alerts. That can pull me out of the moment, notifications are saved though and few things require immediate attention

The notebook turned out to be the key to getting this to work. The biggest hurdle was being afraid that I would forget the very important task that I just remembered – thus I’d be in Outlook calendaring it, and there’d be an email in need of a response or a reminder of another task and so on. Having a designated holding cell alleviated that issue (and it turned out it needed to be a dedicated notebook, not just a piece of paper).

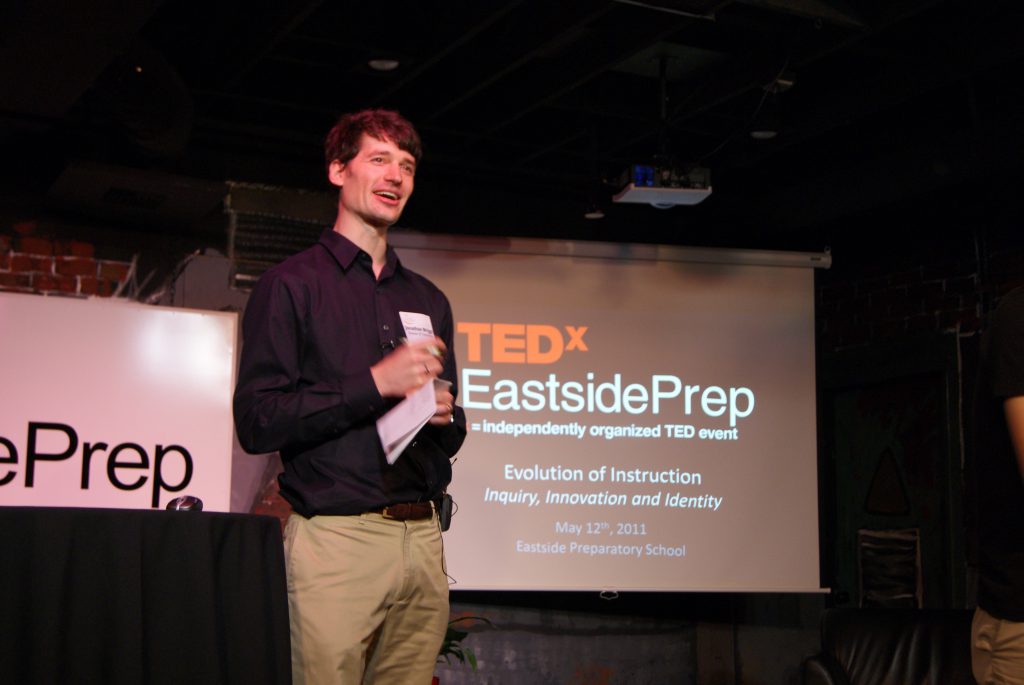

On the presenting side of things, after going to a couple of conferences as only an audience member, I discovered that it was far more engaging if I was also a presenter. You could still see most of the other people who gave talks and you would build a small cohort of people who saw you present and they would talk with you in the halls between sessions. That made everything more interesting and engaging. In contrast to internal PD days, I also leave sessions that are not delivering what I expected and travel to other ones (and invite my audiences to do the same).

Sometimes these sessions pay back by increasing connections with other companies and educators in the area, sometimes they do not. However, the process of explaining what happens at Eastside Prep to an audience that has no context is a valuable exercise that solidifies your own understanding and makes it easier to talk about the school with anyone outside of the community.

Below, you can find a listing of internal and external presentations that I have done that reference education, omitting some of the more mundane ones. Where available, I have included slides and video.

It is also important to note, for those aspiring to talk at a conference, that conferences prefer to greenlight presenters who have presented previously and even then, I’ve had plenty of talks rejected as well.